"Why Was My Teacher a Poor Student?"

Improve American K-12 Education by Recruiting Teachers from the "Top of the Class"

The reputation and standing of the American K-12 teaching profession is collapsing, according to a study published in November 2022. Authors Matthew Kraft of Brown University and Melissa Arnold Lyon of the University of Albany warn that “perceptions of teacher prestige [have] fallen to the lowest levels recorded in the last half century.” This collapse is discouraging top candidates from becoming teachers and pushing other quality teachers out, thereby hastening the profession’s decline and reducing the quality of education for American children.

Many school districts are responding to the teacher shortage exacerbated by COVID and vitriolic politics by lowering hiring standards for teachers even further. While the need to put teachers in classrooms is urgent and understandable in the short-term, lowering standards is exactly the wrong response in the medium- and long-term if we want to ensure we are raising Americans well by giving them the best possible teachers. To slow and eventually reverse the decline in the teaching profession, we should focus on hiring teachers who were once top quality students themselves – “A” students for shorthand. Hiring teachers from “the top of the class” – who also have character and hearts for children – will provide students with stronger and more effective academic role models.

To be sure, there are undoubtedly some successful teachers who were not “A” students, and there are certainly “C” students who go on to enjoy extraordinary careers.

During my undergraduate years at Stanford in the last millennium, students fearing the dreaded “C” (including me) would often cite how an American Nobel laureate and former Stanford student named John Steinbeck (who did not graduate and said his Stanford education was a waste other than what he learned from two English professors) earned a “C” in freshman English and still turned out okay. We found fleeting comfort in the remote possibility that a “C” in English might actually signal budding literary genius rather than just average performance.

To be honest, however, the “C” usually signaled the latter.

Steinbeck succeeded professionally as a writer despite his “C” in freshman English. And he is not the only former “C” student who has gone on to a successful career. There are always exceptions. But if we are honest, all other things being equal, most parents would likely prefer a former “A” student teaching their child rather than a teacher who struggled in school.

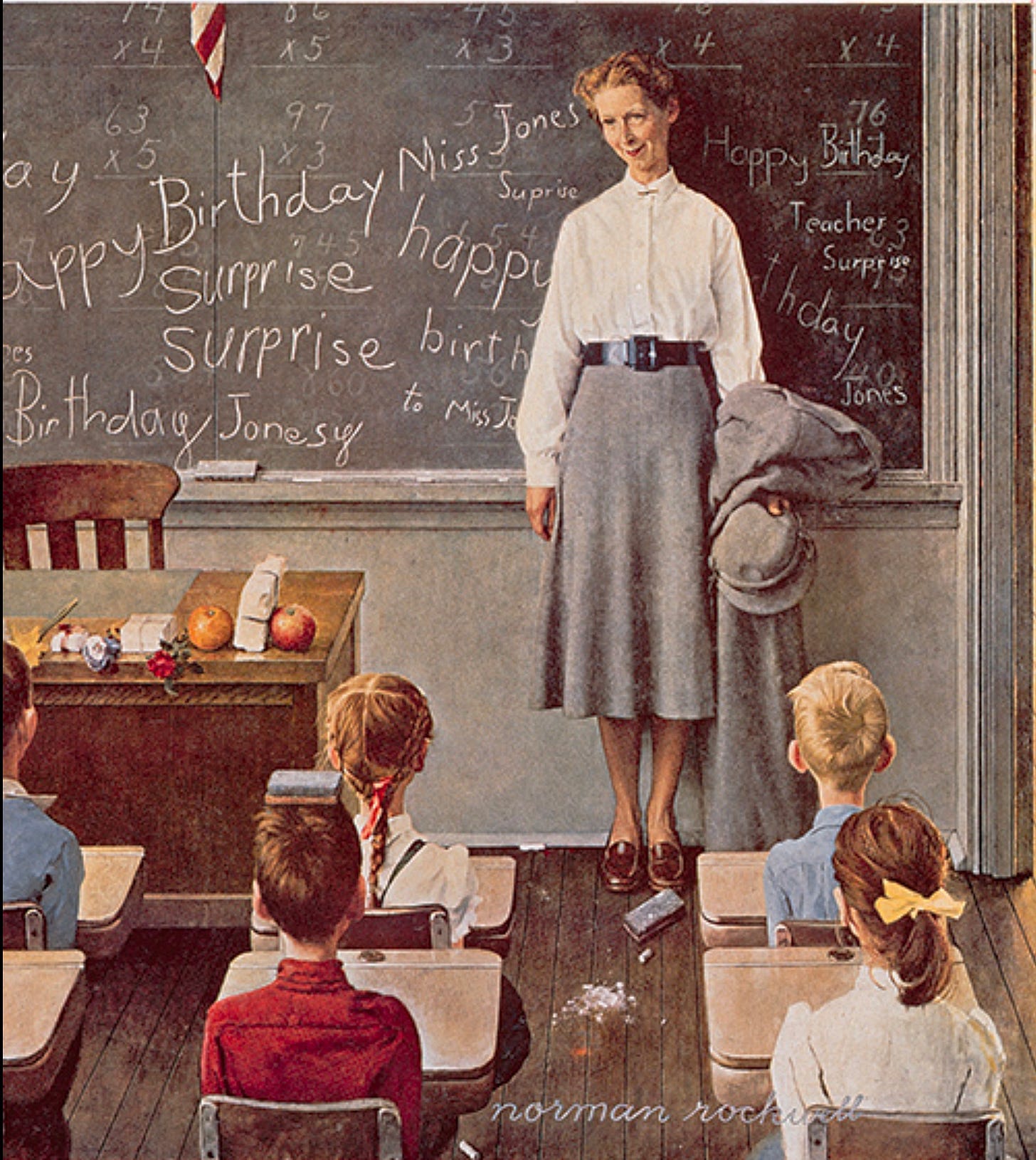

Despite his negative attitude about attending college, Steinbeck, in his epic novel East of Eden, set in the early 20th century American West, pens a passage that reflects a seemingly alien attitude with respect to the teaching profession:

In the country the repository of art and science was the school, and the schoolteacher shielded and carried the torch of learning and of beauty…. The teacher was not only an intellectual paragon and a social leader, but also the matrimonial catch of the countryside. A family could indeed walk proudly if a son married the schoolteacher. (140)

Fareed Zakaria, in a 2018 article entitled “Teachers Need a Lot More Than Appreciation,” echoed my impression when he described Steinbeck’s scene as “almost unrecognizable in today’s America.”

My goodness, we have come a long way.

Considering how America’s 3.7 million teachers “collectively shape the democratic ideals, social cohesion, and economic competitiveness of the nation as a whole,” the authors of the Brown University study claim their findings “should be cause for serious national concern.”

Though it may be difficult for many of us to hear, if we agree students deserve to learn from the best qualified teachers, then it logically follows that assuming good character and a heart for children, schools should be hiring teachers who have themselves been the best students.

It’s just common sense.

If you were learning to fly an airplane, would you want a flight instructor who had excelled in flight school or one who had barely graduated from flight schools with “C” grades because of difficulties learning how to land the plane?

If you were going into surgery, would you rather have a surgeon who got an “A” or “C” average in medical school?

Some might dismiss such examples as extreme. But wouldn’t most of us say the well-being of our children is more important than our own well-being? If that is true, then why do we insist on “A” treatment for ourselves and passively accept up to twelve or thirteen years of “C” treatment for our children?

“A” students know better how to navigate academic challenges and take full advantage of being a student because they have done it themselves. They are more likely to be skilled at helping students excel at school because they were “good” at school. They value academic success, know what is necessary, and enjoy sharing what they have learned about achieving with others.

It may sound shocking, but I have been in more than one teacher’s lounge where teachers with a “C” profile have dismissively belittled a student of theirs who happens to be striving for excellence and dreaming big for their futures. Is that the kind of person you want spending hundreds of hours with your children during some of their most impressionable stages?

To be sure, some “A” students are or would be horrible teachers. An individual, though gifted academically, who doesn’t really enjoy working with kids or who frightens them with an authoritarian air should not be in the classroom. Similarly, the teacher with a sterling academic record who is only interested in kids who are part of her fan club don’t belong in schools either. And there will inevitably be a teacher and former “A” student who lacks character, and perhaps even harms children. We should keep such individuals far from schools.

But generally speaking, the best teacher is one who has character, heart, and a strong academic record and can share lessons and provide guidance rooted in their own successful academic experience. Such a teacher can teach students invaluable skills, attitudes, approaches, and content. Students are less likely to learn from a teacher who did not enjoy the same academic success.

And the sad reality is that too many American K-12 educators are not “A” students.

In 2010, McKinsey and Company, in its publication Closing the Talent Gap: Attracting and Retaining Top-Third graduates to Careers in Teaching, reported half of new teachers are from the bottom third, as indicated by SAT scores. In the years following McKinsey’s report, critics have argued for a rosier picture, the rosiest being that by 2008, the average teacher scored in the 48th percentile on the SAT, which still means that more than half of test takers scored higher than the average teacher. Not exactly rosy either.

Below 50% usually equals a fail in most teachers’ gradebooks.

One does not need to be an “A” student to understand why our schools and children might be struggling if such an unacceptably large portion of K-12 educators struggled in school themselves.

In my first Raising Americans article on December 22, I noted that many of us proudly proclaim that “our children come first,” asking whether that was really the case.

The willingness of so many Americans to simply shrug in the face of such evidence regarding the poor quality of too many teachers in the U.S. suggests we have some work to do to narrow the gap between our words and actions.

Until the next post!

-Antonette